The Julia programming language has wonderful flexibility with types, and this allows you to combine packages in unanticipated ways to solve new kinds of problems. Crucially, it achieves this flexibility without sacrificing runtime performance. It does this by running versions of code or algorithms that have been "specialized" for the specific types you are using. Creating these specializations is compilation, and when done on the fly (as is common in Julia) this is called "just in time" (JIT) compilation. Unfortunately, JIT-compilation takes time, and this contributes to latency when you first run Julia code. This problem is often summarized as "time-to-first-plot," though there is nothing specific about plotting other than the fact that plotting libraries tend to involve large code bases, and these must be JIT-compiled.

Many people have spent a lot of time analyzing and reducing Julia's latency. These efforts have met with considerable success: Julia 1.5 feels snappier than any version in memory, and benchmarks support that impression. But the job of reducing latency is not over yet. Recent work on Julia's master branch has made considerable progress in significantly reducing a specific source of latency, method invalidation. This post will answer questions such as:

What is method invalidation?

How can I diagnose why my code is being invalidated?

How can I fix my code to prevent invalidation?

What impact have the efforts so far had on latency to load and use packages?

Method invalidation: what is it and when does it happen?

An example: compilation for containers with unknown element types

When Julia compiles a method for specific types, it saves the resulting code so that it can be used by any caller. This is crucial to performance, because it means that compilation generally has to be done only once for a specific type. To keep things really simple, we'll use a very artificial example.

f(x::Int) = 1

applyf(container) = f(container[1])Here we've defined two functions; f supports Int, and applyf supports Any argument at all. When you call applyf, Julia will compile specialized versions on demand for the particular types of container that you're using at that moment, even though there isn't any type annotation in its definition. These versions that have been specialized for particular input types are MethodInstances, an internal type in Core.Compiler.

If you call applyf([100]), Julia will compile and use a version of applyf specifically created for Vector{Int}. Since the element type (Int) is a part of the container's type, it will compile this specialization knowing that only f(::Int) will be used: the call will be "hard-wired" into the code that Julia produces. You can see this using @code_typed:

julia> applyf([100])

1

julia> @code_typed applyf([100])

CodeInfo(

1 ─ Base.arrayref(true, container, 1)::Int64

└── return 1

) => Int64The compiler knows that the answer will be 1, as long as the input array has an element indexable by 1. (That arrayref statement enforces bounds-checking, and ensure that Julia will throw an appropriate error if you pass applyf an empty container.)

For the purpose of this blog post, things start to get especially interesting if we use a container that can store elements with different types (here, type Any):

julia> c = Any[100];

julia> applyf(c)

1

julia> @code_typed applyf(c)

CodeInfo(

1 ─ %1 = Base.arrayref(true, container, 1)::Any

│ %2 = (isa)(%1, Int64)::Bool

└── goto #3 if not %2

2 ─ goto #4

3 ─ %5 = Main.f(%1)::Core.Const(1, false)

└── goto #4

4 ┄ %7 = φ (#2 => 1, #3 => %5)::Core.Const(1, false)

└── return %7

) => Int64This may seem a lot more complicated, but the take-home message is actually quite simple. First, look at that arrayref statement: it is annotated ::Any, meaning that Julia can't predict in advance what it will return. Immediately after the reference, notice the isa statement followed by a φ; including the final return, all of this is essentially equivalent to:

if isa(x, Int)

value = 1

else

value = f(x)::Int

end

return valueThe compiler might not know in advance what type container[1] will have, but it knows there's a method of f specialized for Int. To improve performance, it checks (as efficiently as possible at runtime) whether that method might be applicable, and if so calls the method it knows. In this case, f just returns a constant, so when applicable the compiler even hard-wires in the return value for you.

However, the compiler also acknowledges the possibility that container[1]won't be an Int. That allows the above code to throw a MethodError:

julia> applyf(Any[true])

ERROR: MethodError: no method matching f(::Type{Bool})

Closest candidates are:

f(::Int64) at REPL[1]:1

[...]That's similar to what happens if we see how a well-typed call gets inferred:

julia> @code_typed applyf([true])

CodeInfo(

1 ─ %1 = Base.getindex(container, 1)::Bool

│ Main.f(%1)::Union{}

└── unreachable

) => Union{}where in this case the compiler knows that the call won't succeed. Calls annotated ::Union{} do not return.

Triggering method invalidation

NOTE: This demo is being run on Julia's master branch (which will become 1.6). Depending on your version of Julia, you might get different results and/or need to define more than one additional method for f to see the outcome shown here.

Julia is interactive: we can define new methods on the fly and try them out. Having already run the above code in our session, let's see what happens when we define a new method for f:

f(::Bool) = 2While the Vector{Int}-typed version of applyf is not changed by this new definition (try it and see), both the Bool-typed version and the untyped version are different than previously:

julia> @code_typed applyf([true])

CodeInfo(

1 ─ Base.arrayref(true, container, 1)::Bool

└── return 2

) => Int64

julia> @code_typed applyf(Any[true])

CodeInfo(

1 ─ %1 = Base.arrayref(true, container, 1)::Any

│ %2 = Main.f(%1)::Int64

└── return %2

) => Int64This shows that defining a new method for f forced recompilation of these MethodInstances.

You can see that Julia no longer uses that optimization checking whether container[1] happens to be an Int. Experience has shown that once a method has a couple of specializations, it may accumulate yet more, and to reduce the amount of recompilation needed Julia quickly abandons attempts to optimize the case handling containers with unknown element types. If you look carefully, you'll notice one remaining optimization: the call to Main.f is type-asserted as Int, since both known methods of f return an Int. This can be a very useful performance optimization for any code that uses the output of applyf. But define two additional methods of f,

julia> f(::String) = 3

f (generic function with 4 methods)

julia> f(::Dict) = 4

f (generic function with 4 methods)

julia> @code_typed applyf(Any[true])

CodeInfo(

1 ─ %1 = Base.arrayref(true, container, 1)::Any

│ %2 = Main.f(%1)::Any

└── return %2

) => Anyand you'll see that even this optimization is now abandoned. This is because checking lots of methods to see if they all return Int is too costly an operation to be worth doing in all cases.

Altogether, apply(::Vector{Any}) has been compiled three times: once when f(::Int) was the only method for f, once where there were two methods, and once when there were four. Had Julia known in advance that we'd end up here, it never would have bothered to compile those intermediate versions; recompilation takes time, and we'd rather avoid spending that time if it's not absolutely necessary. Fortunately, from where we are now Julia has stopped making assumptions about how many methods of f there will be, so from this point forward we won't need to recompile applyf for a Vector{Any} even if we define further methods of f.

Recompilation is triggered by two events:

when a new method is defined, old compiled methods that made now-incorrect assumptions get invalidated

when no valid compiled method can be found to handle a call, Julia (re)compiles the necessary code.

It's the moment of method definition, triggering invalidations of other previously-compiled code, that will be the focus of this blog post.

How common is method invalidation?

Unfortunately, method invalidation is (or rather, used to be) pretty common. First, let's get some baseline statistics. Using the MethodAnalysis package, you can find out that a fresh Julia session has approximately 50,000 MethodInstances tucked away in its cache (more precisely, about 56,000 on Julia 1.5, about 45,000 on Julia 1.6). These are mostly for Base and the standard libraries. (There are some additional MethodInstances that get created to load the MethodAnalysis package and do this analysis, but these are surely a very small fraction of the total.)

Using SnoopCompile, we can count the number of invalidations triggered by loading various packages into a fresh Julia session:

| Package | Version | # inv., Julia 1.5 | # inv., master branch |

|---|---|---|---|

| Example | 0.5.3 | 0 | 0 |

| Revise | 2.7.3 | 23 | 0 |

| FixedPointNumbers | 0.8.4 | 335 | 0 |

| StaticArrays | 0.12.4 | 2181 | 44 |

| Images | 0.22.4 | 2881 | 301 |

| Optim | 0.22.0 | 2902 | 59 |

| SIMD | 2.8.0 | 2949 | 11 |

| Plots | 1.5.8 | 3156 | 118 |

| Makie | 0.11.1 | 3273 | 129 |

| Flux | 0.10.4 | 3461 | x |

| DataFrames | 0.21.6 | 4126 | 2390 |

| JuMP | 0.21.3 | 4281 | 1952 |

| DifferentialEquations | 6.15.0 | 6373 | 2309 |

('x' indicates that the package cannot be loaded. Julia's master-branch results were at commit 1c9c24170c53273832088431de99fe19247af172, partway through the development of Julia 1.6.)

You can see that key packages used by large portions of the Julia ecosystem have historically invalidated hundreds or thousands of MethodInstances, sometimes more than 10% of the total number of MethodInstances present before loading the package. The situation has been dramatically improved on Julia 1.6, but there remains more work left to do, especially for particular packages.

What are the impacts of method invalidation?

The next time you want to call functionality that gets invalidated, you have to wait for recompilation. We can illustrate this on Julia 1.5 using everyone's favorite example, plotting:

julia> using Plots

julia> @time display(plot(rand(5)))

7.717729 seconds (15.27 M allocations: 797.207 MiB, 3.59% gc time)As is well known, it's much faster the second time, because it's already compiled:

julia> @time display(plot(rand(5)))

0.311226 seconds (19.93 k allocations: 775.055 KiB)Moreover, if you decide you want some additional functionality via

julia> using StaticArrays

julia> @time display(plot(rand(5)))

0.305394 seconds (19.96 k allocations: 781.836 KiB)you can see it's essentially as fast again. However, StaticArrays was already present because it gets loaded internally by Plots–-all the invalidations it causes have already happened before we issued that second plotting command. Let's contrast that with what happens if you load a package that does a lot of new invalidation (again, this is on Julia versions 1.5 and below):

julia> using SIMD

julia> @time display(plot(rand(5)))

7.238336 seconds (26.50 M allocations: 1.338 GiB, 7.88% gc time)Because so much got invalidated by loading SIMD, Julia had to recompile many methods before it could once again produce a plot, so that "time to second plot" was nearly as bad as "time to first plot."

This doesn't just affect plotting or packages. For example, loading packages could transiently make the REPL, the next Pkg update, or the next call to a distributed worker lag for several seconds.

You can minimize some of the costs of invalidation by loading all packages at the outset–if all invalidations happen before you start compiling very much code, then the first compilation already takes the full suite of methods into account.

On versions of Julia up to and including 1.5, package load time was substantially increased by invalidation. On Julia 1.6, invalidation only rarely affects package load times, largely because Pkg and the loading code have been made more resistant to invalidation.

Can and should this be fixed?

Invalidations affect latency on their own, but they also impact other potential strategies for reducing latency. For example, julia creates "precompile" (*.ji) files to speed up package usage. Currently, it saves type-inferred but not native code to its precompile files. In principle, we could greatly reduce latency by also saving native code, since that would eliminate the need to do any compilation at all. However, this strategy would be ineffective if most of this code ends up getting invalidated. Indeed, it could make latency even worse, because you're doing work (loading more stuff from disk) without much reward. However, if we get rid of most invalidations, then we can expect to get more benefit from caching native code, and so if the community eliminates most invalidations then it begins to make much more sense to work to develop this new capability.

As to "can invalidations be fixed?", that depends on the goal. We will never get rid of invalidation altogether; as the applyf example above shows, invalidation is sometimes necessary if you want both good runtime performance and interactive usage, and this combination is one of the best things about Julia. The real question is whether there are unnecessary invalidations, or an unexploited strategy to limit their impact. While the table above resoundingly demonstrates the feasibility of reducing the frequency of invalidation, going any further requires that we develop an understanding the common sources of invalidation and what can be done to fix them.

Changes in Julia that have reduced the number of invalidations

Much of the progress in reducing invalidations in Julia 1.6 come from changes to generic mechanisms in the compiler. A crucial change was the realization that some invalidations were formerly triggered by new methods of ambiguous specificity for particular argument combinations; since calling a function with this argument combination would have resulted in a MethodError anyway, it is unnecessary to invalidate their (nominal) dependents.

Another pair of fundamental changes led to subtle but significant alterations in how much Julia specializes poorly-inferred code to reflect the current state of the world. By making Julia less eager to specialize in such circumstances, huge swaths of the package ecosystem became more robust against invalidation.

Finally, as demonstrated by the applyf example, the version that was well-inferred from the outset–when we passed it container = [100], a Vector{Int}–never needed to be invalidated; it was only those MethodInstances compiled for Vector{Any} that needed updating. So the last major component of how we've reduced invalidations is to improve the inferrability of Julia's own code. By recording and analyzing invalidations, we gained a much better understanding of where the weaknesses in Julia's own code were with respect to inferrability. We used this information to improve the implementations of dozens of methods, and added type annotations in many more, to help Julia generate better code. You find many examples by searching for the latency tag among closed pull requests.

It's worth noting that the task of improving code is never finished, and this is true here as well. In tackling this problem we ended up developing a number of new tools to analyze the source of invalidations and fix the corresponding inference problems. We briefly touch on this final topic below.

Tools for analyzing and fixing invalidations

Recently, the SnoopCompile package gained the ability to analyze invalidations and help developers fix them. Because these tools will likely change over time, this blog post will only scratch the surface; people who want to help fix invalidations are encouraged to read SnoopCompile's documentation for further detail. There is also a video available with a live-session fixing a real-world invalidation, which might serve as a useful example.

But to give you a taste of what this looks like, here are a couple of screenshots. These were taken in Julia's REPL, but you can also use these tools in vscode or other environments.

First, let's look at a simple way (one that is not always precisely accurate, see SnoopCompile's documentation) to collect data on a package:

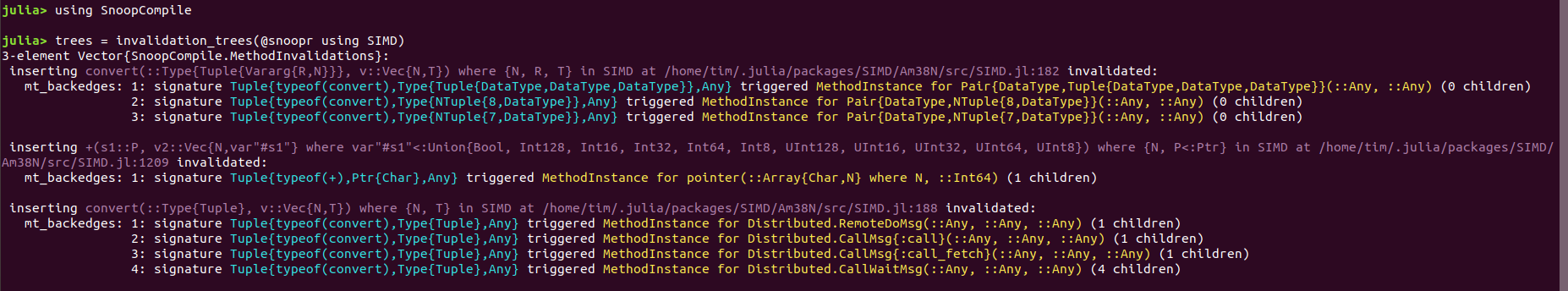

using SnoopCompile

trees = invalidation_trees(@snoopr using SIMD)which in the REPL looks like this:

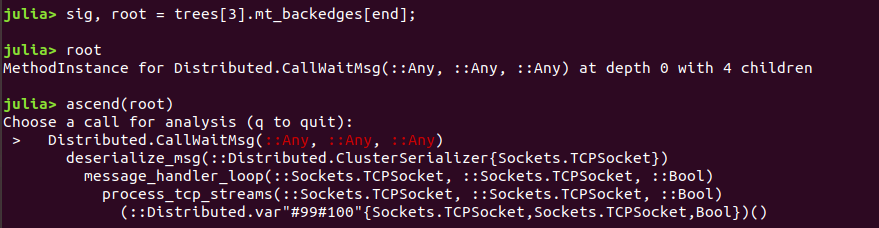

This prints out a list of method definitions (shown in light purple) that triggered invalidations (shown in yellow). In very rough terms, you can tell how "important" these are by the number of children; the ones with more children are listed last. You can gain more insight into exactly what happened, and what the consequences were, with ascend:

The SnoopCompile documentation has information about how to navigate this interactive menu, and how to interpret the results to identify a fix, but in very rough terms what's happening is that deserialize_msg is creating a Distributed.CallWaitMsg with very poor a priori type information (all arguments are inferred to be of type Any); since the args field of a CallWaitMsg must be a Tuple, and because inference doesn't know that the supplied argument is already a Tuple, it calls convert(Tuple, args) so as to ensure it can construct the CallWaitMsg object. But SIMD defines a new convert(Tuple, v::Vec) method which has greater specificity, and so loading the SIMD package triggers invalidation of everything that depends on the less-specific method convert(Tuple, ::Any).

As is usually the case, there are several ways to fix this: we could drop the ::Tuple in the definition of struct CallWaitMsg, because there's no need to call convert if the object is already known to have the correct type (which would be Any if we dropped the field type-specification, and Any is not restrictive). Alternatively, we could keep the ::Tuple in the type-specification, and use external knowledge that we have and assert that args is already a Tuple in deserialize_msg where it calls CallWaitMsg, thus informing Julia that it can afford to skip the call to convert. This is intended only as a taste of what's involved in fixing invalidations; more extensive descriptions are available in SnoopCompile's documentation and the video.

But it also conveys an important point: most invalidations come from poorly-inferred code, so by fixing invalidations you're often improving quality in other ways. Julia's performance tips page has a wealth of good advice about avoiding non-inferable code, and in particular cases (where you might know more about the types than inference is able to determine on its own) you can help inference by adding type-assertions. Again, some of the recently-merged "latency" pull requests to Julia might serve as instructive examples.

Summary

Impacts of progress to date

The cumulative impact of these and other changes over the course of the development (so far) of Julia 1.6 is noticeable. For example, on Julia 1.5 we have extra latencies to load the next package (due to the loading code being invalidated) and to execute already-compiled code if it gets invalidated by loading other packages:

julia> @time using Plots

7.252560 seconds (13.27 M allocations: 792.701 MiB, 3.19% gc time)

julia> @time using Example

0.698413 seconds (1.60 M allocations: 79.200 MiB, 4.90% gc time)

julia> @time display(plot(rand(5)))

6.605240 seconds (11.02 M allocations: 568.698 MiB, 1.75% gc time)

julia> using SIMD

julia> @time display(plot(rand(5)))

5.724359 seconds (16.36 M allocations: 825.491 MiB, 7.77% gc time)In contrast, on the current development branch of Julia pre-1.6 (commit 1c9c24170c53273832088431de99fe19247af172), we have

julia> @time using Plots

3.133783 seconds (7.49 M allocations: 526.797 MiB, 6.90% gc time)

julia> @time using Example

0.002499 seconds (2.69 k allocations: 193.344 KiB)

julia> @time display(plot(rand(5)))

5.481113 seconds (9.71 M allocations: 562.839 MiB, 2.28% gc time)

julia> using SIMD

julia> @time display(plot(rand(5)))

0.115085 seconds (395.11 k allocations: 22.646 MiB)You can see that the first load is dramatically faster, an effect that is partly but not completely due to reduction in invalidations (reducing invalidations helped by preventing sequential invalidation of the loading code itself as Julia loads the sequence of packages needed for Plots). This effect is illustrated clearly by the load of Example, which on Julia 1.5 led to another 0.7s worth of recompilation due to invalidations triggered by loading Plots; on Julia's master branch, this cost is gone because Plots does not invalidate the loading code.

Likewise, the second call to display(plot(...)) is much faster, because loading SIMD did not extensively invalidate crucial code compiled for plotting.

Perhaps the biggest mystery is, why is the first usage faster? There likely to be several contributions:

improvements in compilation speed on Julia 1.6 (a separate line of work worthy of its own blog post)

with less invalidation, some Base code exploited by plotting may not need recompilation

with less invalidation, more

precompilestatements for Plots' own internal methods can be used

As an example of the latter two, on Julia 1.5 the most expensive call to infer during the display(plot(...)) call (which you can measure with SnoopCompile's @snoopi macro) is recipe_pipeline!(::Plots.Plot{Plots.GRBackend}, ::Dict{Symbol,Any}, ::Tuple{Array{Float64,1}})), which by itself requires nearly 0.4s of inference time. Plot actually attempts to precompile this statement, but it can't benefit from the result because some of the code that this statement depends on gets invalidated by loading Plots. On Julia's master branch, this inference doesn't need to happen because the precompiled code is still valid.

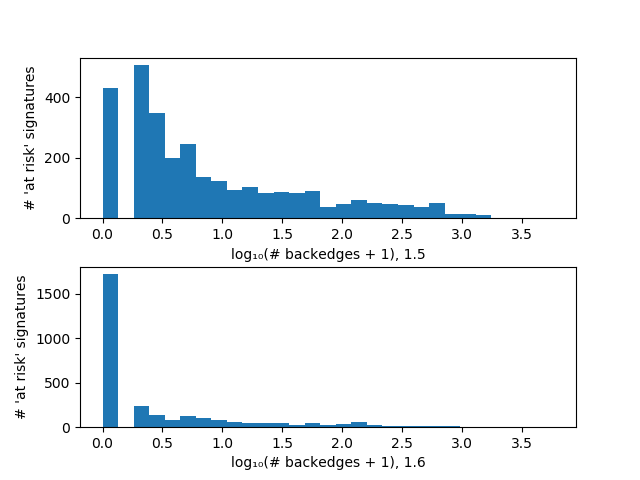

There's another way to get a more comprehensive look at the state of Julia and the progress since 1.5: since most invalidations come from poorly-inferred code, we can analyze all extant MethodInstances and determine which ones have been inferred for "problematic" signatures (e.g., isequal(::Int, ::Any) when we'd prefer a concrete type for the second argument). Aside from counting them, it's also worth noting how many other MethodInstances depend on these "bad" MethodInstances and would therefore be invalidated if we happened to define the right (or wrong) new method. Below is a histogram tallying the number of dependents for each problematic inferred signature, comparing Julia 1.5 (top) with the master branch (bottom):

The very large zero bin for the master branch indicates that many of the problematic signatures on Julia 1.5 do not even appear in master's precompiled code. This plot reveals extensive progress, but that tail suggests that the effort is not yet done.

Outlook for the future

Julia's remarkable flexibility and outstanding code-generation open many new horizons. These advantages come with a few costs, and here we've explored one of them, method invalidation. While Julia's core developers have been aware of its cost for a long time, we're only now starting to get tools to analyze it in a manner suitable for a larger population of users and developers. Because it's not been easy to measure previously, there are still numerous opportunities for improvement waiting to be discovered. In particular, while Base Julia and its standard libraries are well along the way to being "protected" from invalidation, the same may not be true of many packages. One might hope that the next period of Julia's development might see significant progress in getting packages to work together gracefully without inadvertently stomping on each other's toes.