After 3 betas and 3 release candidates, Julia version 1.10 has finally(!) been released. We would like to thank all the contributors to this release and all the testers that helped with finding regressions and issues in the pre-releases. Without you, this release would not have been possible.

The full list of changes can be found in the NEWS file, but here we'll give a more in-depth overview of some of the release highlights.

- New parser written in Julia

- Package load time improvements

- Improvements in stacktrace rendering

- Parallel garbage collection

- Tracy and Intel VTune ITTAPI profiling integration

- Upgrade to LLVM 15

- Linux AArch64 stability improvements

- Parallel native code generation for system images and package images

- Avoiding races during parallel precompilation

- Parallel precompile on using

- Acknowledgement

New parser written in Julia

Claire Foster

With the release of Julia 1.10, swapped out the default parser, previously written in Scheme, to a new one, written in Julia, known as JuliaSyntax.jl. This change introduces several improvements:

Increased Parsing Performance: The new parser has significantly better performance for parsing code.

Detailed Syntax Error Messages: Error messages now provide more specific information, pinpointing the exact location of syntax issues.

Advanced Source Code Mapping: The parser generates expressions that track their position in the source code, facilitating precise error localization and being useful to build tools like linters on top of.

An example to illustrate the improvement in error messaging:

Pre Julia 1.10 Error Message:

julia> [[], [], [,] [], []]

ERROR: syntax: unexpected ","In this version, the error message is general and doesn't specify the location of the syntax error.

Julia 1.10 Error Message:

julia> [[], [], [,] [], []]

ERROR: ParseError:

# Error @ REPL[1]:1:11

[[], [], [,] [], []]

# ╙ ── unexpected `,`Here, the error message includes an indication of the exact location of the issue within the code.

For a more detailed overview of the new parser, you can refer to this 2022 JuliaCon talk.

Package load time improvements

Jameson Nash et al.

In 1.9 the TTFX (Time To First X, the time it takes for the result to be available the first time a function is called) was heavily improved by allowing package authors to enable saving of native code during precompilation. In 1.10, as a follow-up, significant work was put into the performance of the loading of packages.

A lot of this work was driven by profiling and improving the load time of OmniPackage.jl which is an artificial "mega package" whose only purpose is to depend on and load a lot of dependencies. In total, OmniPackage.jl ends up loading about 650 packages, many of them of significant size.

Among many other things

Improvement to the type system that caused it to scale better as the number of methods and types got large.

Reduction in invalidations that trigger unnecessary recompilation.

Moving packages away from Requires.jl to package extensions (which can be precompiled).

Optimizations in

mul!dispatch mechanisms.Numerous other performance upgrades.

Running @time using OmniPackage (after precompilation) has the following results on 1.9 and 1.10 respectively (measurements made on an M1 Macbook Pro):

# Julia 1.9:

48.041773 seconds (102.17 M allocations: 6.522 GiB, 5.82% gc time, 1.21% compilation time: 86% of which was recompilation)

# Julia 1.10:

19.125309 seconds (30.38 M allocations: 2.011 GiB, 11.54% gc time, 10.38% compilation time: 61% of which was recompilation)So this is more than a 2x package load improvement for a very big package. Individual packages may seem smaller or larger improvements.

Improvements in stacktrace rendering

Jeff Bezanson, Tim Holy, Kristoffer Carlsson

When an error occurs Julia prints out the error together with a "stacktrace" aimed to help at debugging how the error occurred. These stacktraces in Julia are quite detailed, containing information like the method name, argument names and types, and the location of the method in the module and file. However, in complex scenarios involving intricate parametric types, a single stacktrace frame could occupy an entire terminal screen. With the Julia 1.10 release, we've introduced improvements to make stacktraces less verbose.

One major factor contributing to lengthy stacktraces is the use of parametric types, especially when these types are nested within each other. This complexity can quickly escalate. To address this, in pull request #49795, the REPL now abbreviates parameters with {…} when these would otherwise be excessively long. Users can view the complete stacktrace by using the show command on the automatically defined err variable in the REPL.

Other notable improvements include:

Omitting the

#unused#variable name in stacktraces. For example,zero(#unused#::Type{Any})now appears aszero(::Type{Any}).Simplifying the display of keyword arguments in function calls. For instance,

f(; x=3, y=2)previously displayed asf(; kw::Base.Pairs{Symbol, Int64, Tuple{Symbol, Symbol}, NamedTuple{(:x, :y), Tuple{Int64, Int64}}})in a stacktrace. Now, it's shown asf(; kw::@Kwargs{x::Int64, y::Int64}), with@Kwargsexpanding to the former format.Collapsing successive frames at the same location. Defining

f(x, y=1)implicitly defines two methods:f(x)(callingf(x, 1)) andf(x, y). The method forf(x)is now omitted in the stacktrace as it exists solely to callf(x, y).Hiding internally generated methods, often created for argument forwarding and bearing obscure names like

#f#16.

To illustrate, consider the following Julia code:

f(g, a; kw...) = error();

@inline f(a; kw...) = f(identity, a; kw...);

f(1)Previously, the stacktrace for this code appeared as:

Stacktrace:

[1] error()

@ Base ./error.jl:44

[2] f(g::Function, a::Int64; kw::Base.Pairs{Symbol, Union{}, Tuple{}, NamedTuple{(), Tuple{}}})

@ Main ./REPL[1]:1

[3] f(g::Function, a::Int64)

@ Main ./REPL[1]:1

[4] #f#16

@ ./REPL[2]:1 [inlined]

[5] f(a::Int64)

@ Main ./REPL[2]:1

[6] top-level scope

@ REPL[6]:1With the improvements in Julia 1.10, the stacktrace is now more concise:

Stacktrace:

[1] error()

@ Base ./error.jl:44

[2] f(g::Function, a::Int64; kw::@Kwargs{})

@ Main ./REPL[1]:1

[3] f(a::Int64)

@ Main ./REPL[2]:1

[4] top-level scope

@ REPL[3]:1This update results in stacktraces that are both shorter and easier to read.

Parallel garbage collection

Diogo Correia Netto, Valentin Churavy

We parallelized in 1.10 the mark phase of the garbage collector (GC) and also introduced the possibility of running part of the sweeping phase concurrently with application threads. This results in significant speedups on GC time for multithreaded allocation-heavy workloads.

The multi-threaded GC can be enabled through the command line option --gcthreads=M, which specifies the number of threads to be used in the mark phase of the GC. One may also enable concurrent page sweeping mentioned above through --gcthreads=M,1, meaning M threads will be used in the GC mark phase and one GC thread is responsible for performing part of the sweeping phase concurrently with the application.

The default number of GC threads is set, by default, to half of the number of compute threads (--threads).

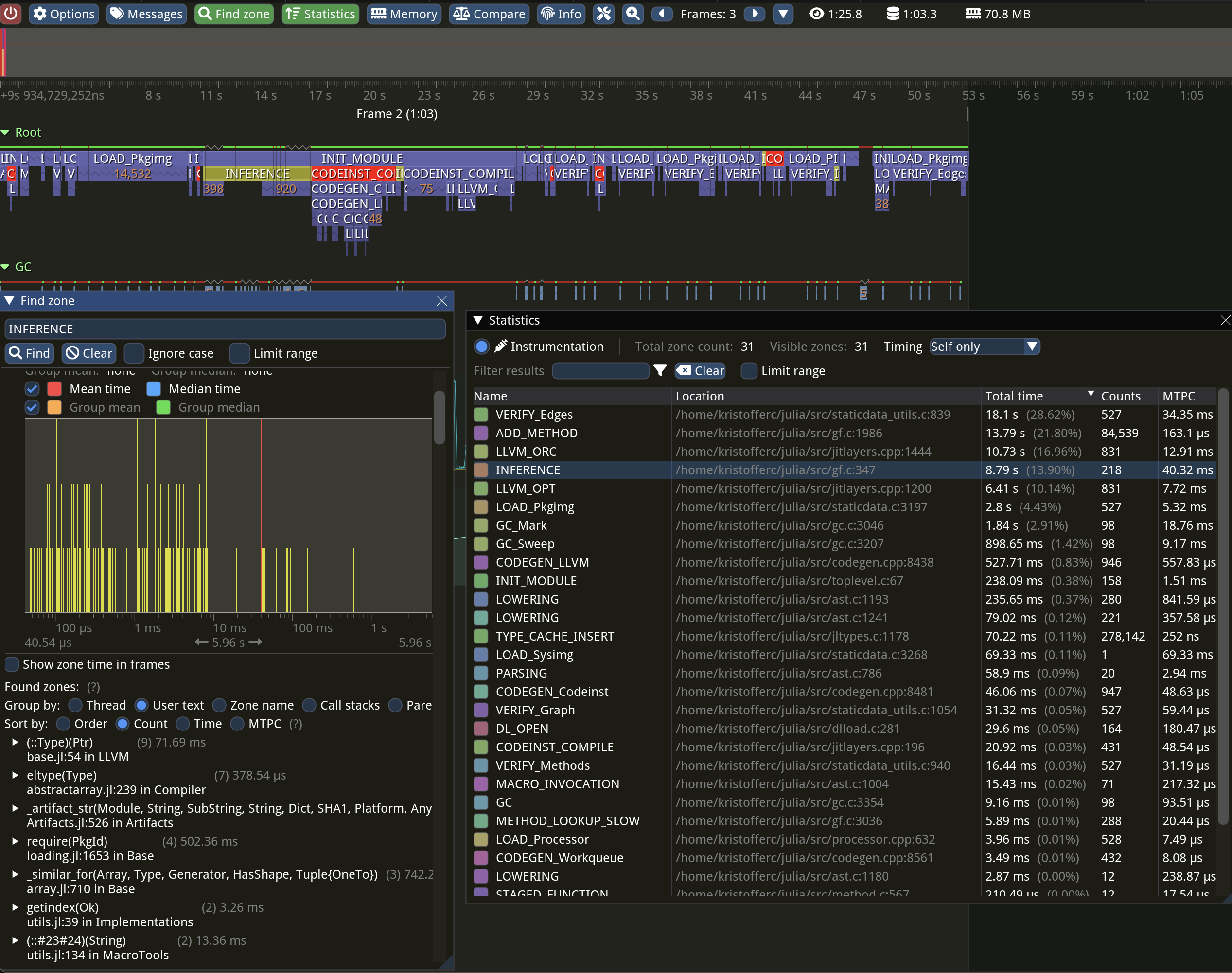

Tracy and Intel VTune ITTAPI profiling integration

Cody Tapscott, Valentin Churavy, Prem Chintalapudi

The Julia runtime has gained additional integration capabilities with the Tracy profiler as well as Intel's VTune profiler. The profilers are now capable of reporting notable events such as compilation, major and minor GCs, invalidation and memory counters, and more. Profiling support can be enabled while building Julia via the WITH_TRACY=1 and WITH_ITTAPI=1 make options. We aim to make these profilers usable without having to rebuild Julia in future Julia versions.

Below is an example of using Tracy when profiling the Julia runtime.

Upgrade to LLVM 15

Valentin Churavy, Gabriel Baraldi, Prem Chintalapudi

We continue to track upstream LLVM and the Julia 1.10 release uses LLVM 15. This brings with it updated profiles for new processors and general modernizations.

Particular noteworthy were the move to the new pass-manager promising compilation time improvements. LLVM 15 brings with it improved support for Float16 on x86.

Linux AArch64 stability improvements

Mose Giordano

With the upgrade to LLVM 15 we were able to use JITLink on aarch64 CPUs on Linux. This linker, which had been first introduced in Julia v1.8 only for Apple Silicon (aarch64 CPUs on macOS), resolves frequent segmentation fault errors that affected Julia on this platform. However, due to a bug in LLVM memory manager, non-trivial workloads may generate too many memory mappings (mmap) that can exceed the limit of allowed mappings. If you run into this problem, read the documentation on how to change the mmap limit.

Parallel native code generation for system images and package images

Prem Chintalapudi

Ahead-of-time compilation (AOT) was sped up by exposing parallelism during the LLVM compilation phase. Instead of compiling a large monolithic compilation unit, the work is now split into multiple smaller chunks. This multithreading speeds up the compilation of system images as well as large package images, resulting in lower precompile times for these.

The amount of parallelism used can be controlled by the environment variable JULIA_IMAGE_THREADS=n. Also, due to the limitations of Windows-native COFF binaries, multithreading is disabled when compiling large images on Windows.

Avoiding races during parallel precompilation

Ian Butterworth

In previous versions of Julia multiple processes running with the same depot will all race to precompile packages into cache files, resulting in extra work being done and the potential for corruption of these cache files.

1.10 introduces a "pidfile" (process id file) locking mechanism that orchestrates it such that only one Julia process will work to precompile a given cache file, where a cache file is specific to the Julia setup that is being targeted during precompilation.

This arrangement benefits both local users, who may be running multiple processes at once, and high-performance computing users who may be running hundreds of workers with the same shared depot.

Parallel precompile on using

Ian Butterworth

While Pkg automatically precompiles dependencies in parallel after installation, precompilation that happens at using/import time has previously been serial, precompiling one dependency at a time.

When developing a package users can end up hitting precompilation during load time, and if code changes in developed packages are deep in the dependency tree of the package being loaded the serial precompile process can be particularly slow.

1.10 introduces parallel precompilation during loading time to catch these cases and precompile faster.

Acknowledgement

The preparation of this release was partially funded by NASA under award 80NSSC22K1740. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.